Notes From The Program Director | Week of April 12th, 2024

Hero Image

Hero Image

heading

Notes From The Program Director

Week of April 12th, 2024

Melissa Tamminga

Rich Text

April 12-18, 2024 This week, the “gleefully maximalist” Love Lies Bleeding and the immigration comedy with quirk and heart, Problemista continue, and there are also two final chances on Saturday and Sunday to see the hilariously fun Hundreds of Beavers, which is delighting crowds in arthouses across the country as well as at the Pickford. As our PFC colleague, Langley West (aka Bloody Uncle Joe, who introduced It’s Alive, our old-timey classic horror series), recently said after attending one of our shows, “You really need to see HUNDREDS OF BEAVERS. It was wonderful to hear an audience all laughing together and applaud at the end of the film. Insane, wacky, slapstick brilliance.” As Langley indicates, it’s truly a one-of-a-kind communal experience and not to be missed. We also have two brand new films beginning their run on our screens this week: Civil War and Here. |

|

Civi War, even before general audiences had seen it, is a film that has generated discussion, even heated discussion. A film by a well-known and respected director, set in a future that imagines civil war in the United States is of course going to generate discussion in these fraught political times, an election year no less. I walked into my own screening of the film genuinely unsure if I would want to program it for the Pickford . . . and I walked out, shaken, but certain it needed to be on our screens.

The film is not an easy one, and I suspect some will decide they won’t want to see it. It is, in many ways, a shattering film. But it’s shattering in the sense that a war film should be if it's going to try to depict war truthfully. Many war films often carry with them a kind of exhilaration for audiences, and much ink has been spilled over the question of whether war movies, by definition, by putting exciting, visceral violence on screen, glorify war in immoral ways. But if any film gets close to making war as uncomfortable as it ought to be, this is it. It’s a film that feels all too real -- or feels that it could very well be real, some 10-15 years or so in the future -- and it’s shown as happening right here on American soil. I’ve not seen or felt anything quite like it.

Civil War is thoroughly effective not just because it hits so close to home and depicts war so shatteringly, it is also extremely well made: stunning production design, beautiful cinematography, a wonderfully unsettling soundtrack, tremendous sound design, lived-in performances (particularly from Kirsten Dunst), finely crafted narrative, consistency of tone, and individual scenes--one after the other--that pack powerful punches.

But I should address one bit of controversy about the film here that has been roiling around cinephile circles and perhaps some of you have read about. When Civil War premiered at the South by Southwest film festival, early reviews offered both enormous praise -- and intense criticism. Many critics adored it, while others hated it and called it "shallow" and "muddled" thematically and morally. And while critical disagreement is to be expected with every film ever made, the controversy in this case really got going when some became outraged by public comments the director, Alex Garland, made during an interview about the film: his comments seemed to indicate he didn't believe there was any difference between the political right and left, and he seemed to embrace a kind of disastrous "both-sides-ism."

He said, "Left and right are ideological arguments about how to run a state. That’s all they are. They are not a right or wrong, or good and bad. It’s which do you think has greater efficacy? That’s it. You try one, and if that doesn’t work out, you vote it out, and you try again a different way. That’s a process. But we’ve made it into ‘good and bad.’ We made it into a moral issue, and it’s f----g idiotic, and incredibly dangerous."

In a world where we are seeing a rise of authoritarianism, fascism, and right-wing extremism, both here and abroad, it’s easy to understand why people were so outraged by his comments, easy to understand why some concluded even before watching the film itself, that its director couldn’t have possibly made a good film about American civil war.

But as Ebert editor Matt Zoller Seitz (who actually watched the film before casting judgment) wisely noted in response to Garland’s comments, "I’m old enough to remember interviews Francis Coppola gave about Apocalypse Now in which he talked about US foreign policy & managed to put both of his feet in his mouth at the same time. Filmmakers are often better off letting pictures do the talking."

And I think Seitz is right: it's better if the film itself, Civil War, does the talking because, as anyone who’s seen the film knows, it simply is not a film that downplays fascism or right-wing extremism -- in fact, the opposite is pretty clearly indicated. But more than that, the film wisely avoids what I think would be a foolhardy attempt to comment on the specifics of American politics and partisanship today. That is not the film’s purpose.

Rather, Civil War is interested in doing three key things, each connected to a thematic inquiry, and I think it does so quite brilliantly: 1) dismantling the notion of American exceptionalism; 2) teasing out the implications of American militarism and our country’s obsession with guns; and 3) probing the presumption of journalistic neutrality and examining the ethics of war photojournalism, particularly the notion that a photo can lead people to both truth and moral goodness.

The first theme is perhaps the least complicated, simply presenting viewers with this: "You think that we’re the ‘good guys’? You think we’re a democratic beacon to the world and that the violence and chaos you've always seen as something other people experience in other countries can't happen here? Think again. Because here is a very realistic depiction of exactly what it could look like here." And the film’s depiction is, indeed, specific, blunt, and powerfully effective.

The second theme powerfully invites viewers to connect the militaristic-global (namely, American military might abroad) to the militaristic-local (namely, private gun ownership and the proliferation of guns on our own soil). The film asks us to look at images that flesh out the implications of those things, and without giving too much away, I’ll note that the very last image of the film (a reference to infamous images connected to the Iraq war) is I believe, a profound and direct assault on the idea of American moral goodness, implying such goodness is impossible in a nation obsessed with militaristic power.

And the third theme is more complicated and endlessly fascinating to me, not just because we depend so heavily on photojournalism now to tell us truths about the world, but also because as film lovers, we believe in the power of the image. We even often believe images have the power of moral clarity and moral action. This film asks us to really examine that belief.

And it's the interrogation into that belief that’s kept me thinking, long after the thudding power of the scenes onscreen had faded.

Our other new film this week, Here, is radically different from Civil War, and while Civil War examines things we should confront, Here is a film that reminds us that kindness resides in our humanity, too.

Here is, simply, "exquisite," to borrow a word our Cinema East contributor Eren Odabasi used when we were discussing the film recently. The story follows a very simple narrative in its spare 82 minute runtime, and its simplicity is a key part of its deep pleasures: Stefan is a Romanian construction worker living in Brussels, and he has decided to go back to his home country, perhaps permanently. We follow him as he's spending his time cleaning his apartment, clearing out his fridge, making a soup from the leftovers to share with local friends. But something undefined is holding him back from taking the final steps to leave Brussels, and his nights are sleepless.

It is in this in-between time, in Stefan's meditative, often-nighttime rambles about the city that has been his home, that he encounters ShuXiu, a Belgian-Chinese scientist, a bryologist, whose doctoral work is to collect, study, and catalog mosses. The unlikely connection between the two -- one immigrant ready to leave, one immigrant content to stay and study the region's plants -- is warm, palpable, and gently evocative.

It is a film that might be "about" many things: migrants within the European Union, the joy of unexpected human connections, the unutterable beauty of the natural world in the midst of the city, the mysterious nature of romance, the poignance of the notion of "home," but like so many of the best films, nothing is explicit even while the emotions imbued in the delicacy of the images are profound. It's a beautiful, gentle film, and as it is paired with Civil War on our other screen, I'll end here with a reflection from director Bas Devos, who, in this film, aimed for something very very different from Garland's film: "I have been looking for narratives that are different and that talk about a way of being together in a non-violent way. Whereas so many of the narratives that we are bombarded with have violent events. Whether it’s emotional violence or just physical violence, it seems to define what human beings are. We bash each other’s heads in, we make each other cry. And I think, ‘Wow, that’s a narrow way of looking at what human beings are,’ because we are much more than that. We are also capable of compassion and of sharing and of creating a space in which people feel welcome and safe. And I think we need these kinds of spaces; I think they are relatively rare." |

We have just two special events this week, but each of them offer unique cinematic joys: Nowhere and The Trouble with Wolves. Nowhere is this month’s selection for our Third Eye film series, “staff-curated cult classics,” and projectionist Anthony Bowmer, who chose the film, writes this about it: “Nowhere is one of the greatest films of the American independent cinema boom of the 90s and a masterpiece of New Queer Cinema. I was thrilled when I saw it was finally getting a new restoration and sought an opportunity to share this under-seen film with a wider audience. Nowhere is a kinetic look at a group of teenagers at the end of the 20th century, filled with lust, violence, apocalyptic dread, aliens, religious cults, and Kafka-esque body horror. It’s a beautiful amalgamation of queer experience that continues to resonate, unabashedly personal and unique, as well as a perfect example of how far gorgeously constructed DIY sets and a rollicking soundtrack can take you.” Join us for Nowhere on Saturday at 10 pm. |

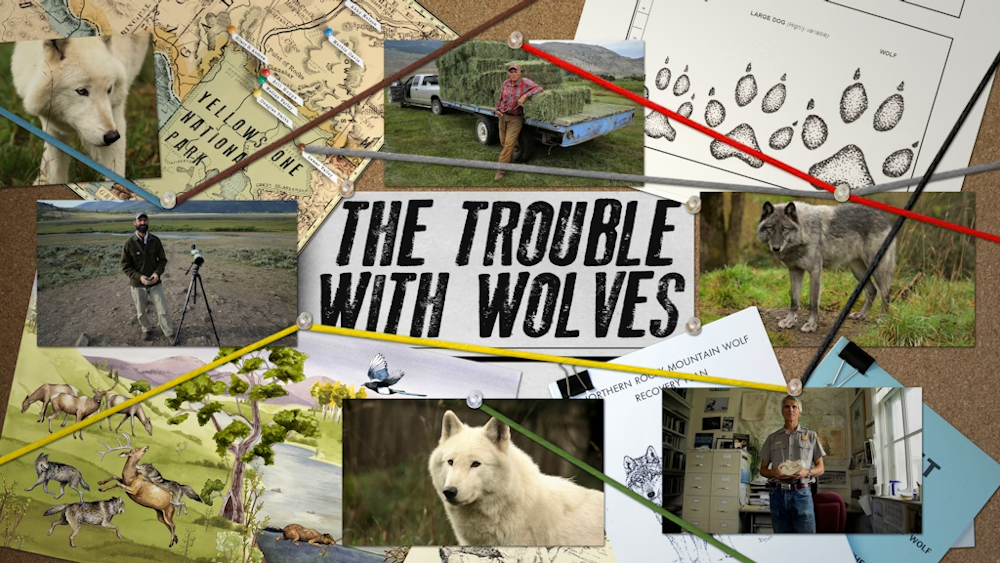

Our screening of The Trouble with Wolves is a rare occasion where we can directly pair cinema with environmental action, and we are grateful for this opportunity. The screening is a by-donation event, and donations will be split between Wolf Haven international and the PFC (to cover operating costs). Located in Tenino, Washington, Wolf Haven International is “an internationally recognized wolf sanctuary that has rescued and provided a lifetime home for over 300 displaced, captive-born animals since 1982 under the mission ‘to conserve and protect wolves and their habitat.’” The film is “an exploration of the complex and often controversial relationship between wolves and humans in the American West,” and it “delves into the challenges and rewards surrounding wolf reintroduction and conservation efforts, highlighting differing viewpoints from livestock producers, conservationists, and wildlife managers.” Join us on Sunday, 1:00 pm, for this special screening; there will be a 30-minute discussion to follow the film, moderated by Wolf Haven staff. See you at the movies, friends! Melissa |

back to blog page button

Marketing Signup

Marketing Signup

site note

We open 30 minutes before the first showtime of the day.

All theaters are ADA accessible with wheelchair seating.

Closed captioning and assistive listening devices are available at the box office.

custom footer

Pickford Film Center

1318 Bay St

Bellingham, WA 98225

Office | 360.647.1300

Movie line | 360.738.0735

Mailing Address

PO Box 2521

Bellingham, WA 98227

Footer