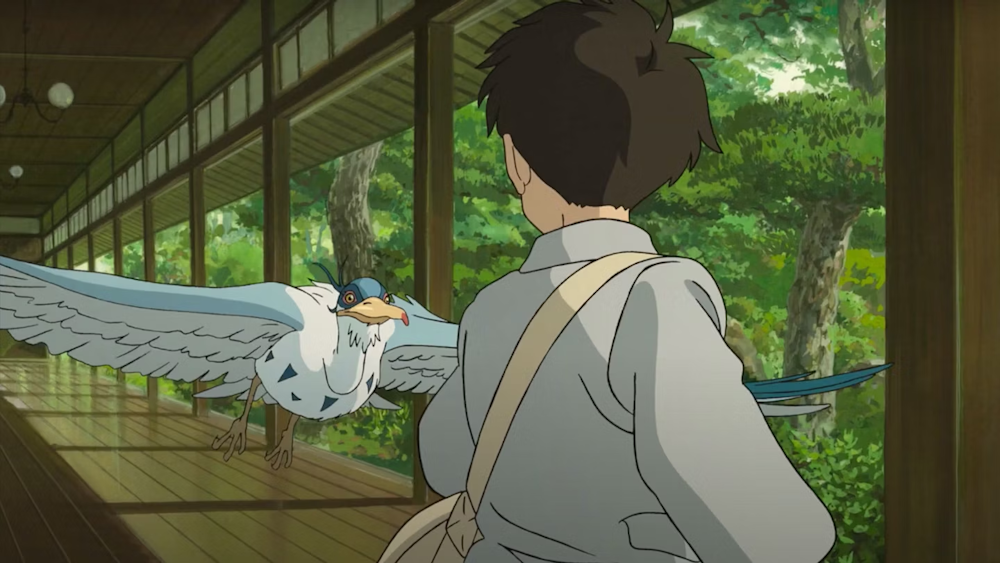

The opening weekend of The Boy and the Heron promises lots of giddy fans (my family among them!) and sold out shows, and we can’t wait to see you all here! Many of you have been following along with our monthly Studio Ghibli series, joining us for our screenings of My Neighbor Totoro, Ponyo, Kiki’s Delivery Service, Nausicaa Valley of the Wind, and Castle in the Sky, and there couldn’t be a better way to prepare for Miyzaki’s newest film, after the long, 10-year wait since his last film (The Wind Rises, 2013). The Boy and the Heron is everything we love and we’ve come to expect from a Studio Ghibli film -- and more. It is the story of a boy who loses his mother to a World War II bombing and while living in the midst of his grief, encounters the grace of the magical: he discovers and enters into another world, a vast, fantastical world, full of surprise, delight, humor, adventure, danger, love, and wisdom. A fantasy world that, in the beautiful Ghibli-way, helps him make sense of the world normally conceived of as reality. Henry David Thoreau famously wrote he “went to the woods,” to commune alone with nature because he “wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life . . . to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms,” and there is something of a similar sense with Miyazaki’s work. Except to watch a Miyazaki film is to suck all the marrow out of life not by reducing it, but by expanding it, to see its glorious multiplicity of facets, a glory that might only be seen when we admit to the magical that lives and breathes just beneath the surface of everyday life--the magic that perhaps children often see better than adults. And this is perhaps the reason that Miyazki’s heroes are most often children--even as his films are a delight for all ages and it’s maybe we adults that need them most.

|

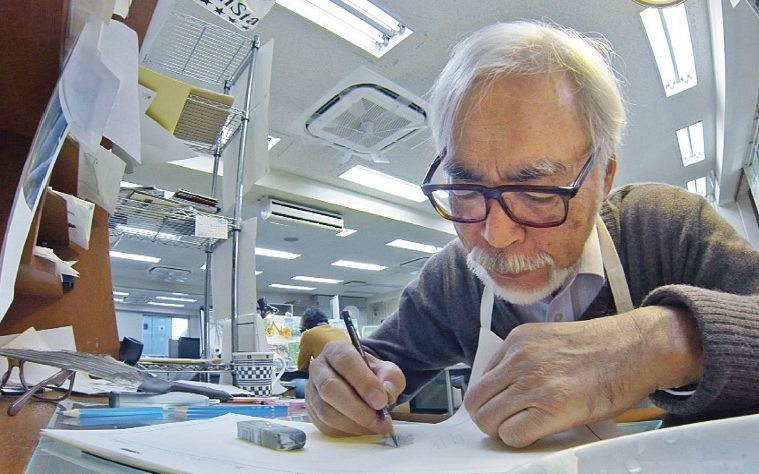

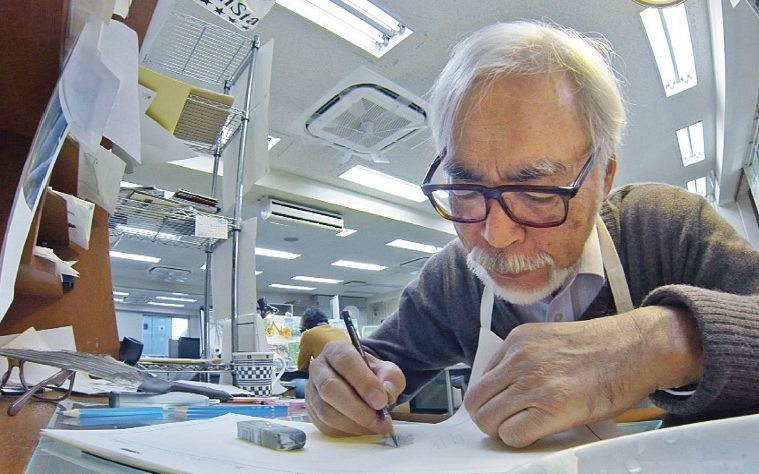

And indeed, there is a profound sense of the mature and autobiographical in this film: Miyazaki reflecting on life--his own life--through the eyes of a boy, but asking questions through the lens of his 82 years. There is a child’s sense of wonder, play, and openness here (a signature of Studio Ghibli), paired with the wisdom of years and age. Miyazaki has said Heron is not his last film, that he’s already working on a new one, but it’s hard to ignore the fleeting nature of time as we consider directors like Miyazaki. How much longer will we have the gift of his artistry with us? It’s a question that, consciously or not, runs through The Boy and the Heron itself, a film whose original Japanese title is How Do You Live? and a film that, with its magical multiplicity, poignantly and beautifully grapples with a world of mortality and change and what it means to live and thrive and love such a world. And so I will close this section with something my film colleague and friend Carlos Valladares wrote in response to The Boy and the Heron, a reflection that I think captures what it means to watch this Miyazaki film at this moment in time: “Is this (in 2023) what it felt like to watch the final films of Ford, Minnelli, Lang, Hitchcock, etc. in 1966? The last Miyazakis, the last Scoreseses, the last Godards, the last Vardas, the last Erices, the last Loaches, the last Bellochhios ... “I’m reminded of Scorsese’s moving complaint in Deadline: “‘I wish I could take a break for eight weeks and make a film at the same time [laughs]. The whole world has opened up to me, but it’s too late. It’s too late. I’m old. I read stuff. I see things. I want to tell stories, and there’s no more time. Kurosawa, when he got his Oscar, when George [Lucas] and Steven [Spielberg] gave it to him, he said, ‘I’m only now beginning to see the possibility of what cinema could be, and it’s too late.’ He was 83. At the time, I said, ‘What does he mean?’ Now I know what he means.’ “Now, Miyazaki, too, finally sees what he can do with cinema: and, it turns out, he is only beginning.”

|

We also have three very special events this week: Christmas in Connecticut, a Third Eye Christmas selection In Bruges, and a Maestro preview screening. Christmas in Connecticut is a practically perfect classic Christmas film: a romantic comedy of the most wonderful farcical nature, with powerhouse Barbara Stanwyck being her most utterly delightful best. She was a to-die-for sexpot femme fatale in the 1944's noir Double Indemnity, but here, in 1945, she proved (again) she could be both hilarious and sexy, like she was in her earlier screwball comedy The Lady Eve in 1941. The premise here is delightful: Stanwyck plays an NYC apartment-dwelling young woman, Elizabeth Lane, who doesn't want and doesn't need the white picket fence, the husband, or the kids, but she's a writer who creates a magazine persona of the "perfect" housewife who has all those things and who lives on a farm cooking all manner of wonderful things. Her weekly magazine column, "Diary of a Housewife," is from the perspective of this fictional housewife, and she shares all her recipes (created by her friend who is a chef) and her housekeeping tips. The snag? Her magazine publisher thinks her persona is real, and he invites a wounded war hero "home" to Elizabeth's "house" for the holidays. And so the delightfully comical farce begins: To keep her job, Elizabeth must pretend she has a house in the country, a baby, a husband, and the cooking know-how to play host to the war hero. One of the most satisfying things about the film -- barring the hilarious cast and their antics -- is the fact that there's never any shame in Stanwyck's character not knowing how to cook, not having children, not being married, nor any suggestion that she'd be a happier or better person if she had those things. The film likes her, it suggests, exactly the way she is. And rather, she's in a farcical situation the film presents, not because she should be different, but because the social expectations put her there. From start to finish, I could not love Christmas in Connecticut more! It will play twice: Saturday, Dec. 9, 1:30, and Sunday, Dec. 10, 10:00 am.

|

Third Eye, our staff-curated cult classics, this month brings us In Bruges, Martin McDonagh’s first brilliant pairing of Brendan Gleeson and Colin Farrell, whom we all so enjoyed last year with The Banshees of Inisherin. For Third Eye this month, we as a staff voted on three “Christmas” films that fall somewhat outside the norm of the usual Christmas fare, appropriate to our Third Eye oeuvre -- In Bruges, Eyes Wide Shut, and The Long Kiss Goodnight -- and In Bruges won the day! So join us and our two hitmen, Ray and Ken, hiding out in Bruges for Christmas, on Saturday, December 9, 10 pm.

|

Finally, Maestro, a new biopic about Leonard Bernstein and his wife Felicia, officially opens on Friday, December 15, but, happily, we have a special advance screening on Thursday, Dec. 14, 7:35 pm. Justin Chang, one of my very favorite critics, offers this tantalizing description in the L.A. Times: "The magnificent new drama Maestro is skilled in the art of multitasking itself, and not just because Cooper directed, produced and (with Josh Singer) co-wrote the movie as well as starring in it. Five years after his filmmaking debut, A Star Is Born, the director has returned with another admirably complicated and generously balanced portrait of a tempestuous showbiz marriage, this one drawn from real life. With narrative elegance, formal brio and exquisite feeling, Cooper ushers Felicia [played by Carey Mulligan] into the spotlight and sometimes shunts the attention-hogging Lenny off into the wings. . . . In doing so, the director offers up a subtle yet significant corrective to some of the dramatic oversights and patriarchal assumptions endemic to the great-man biopic." What a rich week for cinema. See you at the movies, friends! Melissa |